“I think the idea of an ‘alternative archive’ is to come at it from a slightly different angle,” says Mandurah-based artist James Walker, who features in The Alternative Archive exhibition.

For James, this meant looking up for inspiration to create Plane Spotting: Traverse 30 Days, a series of paintings that contemplates how “the empty space in the sky is as important as all the clutter you might see on the ground”.

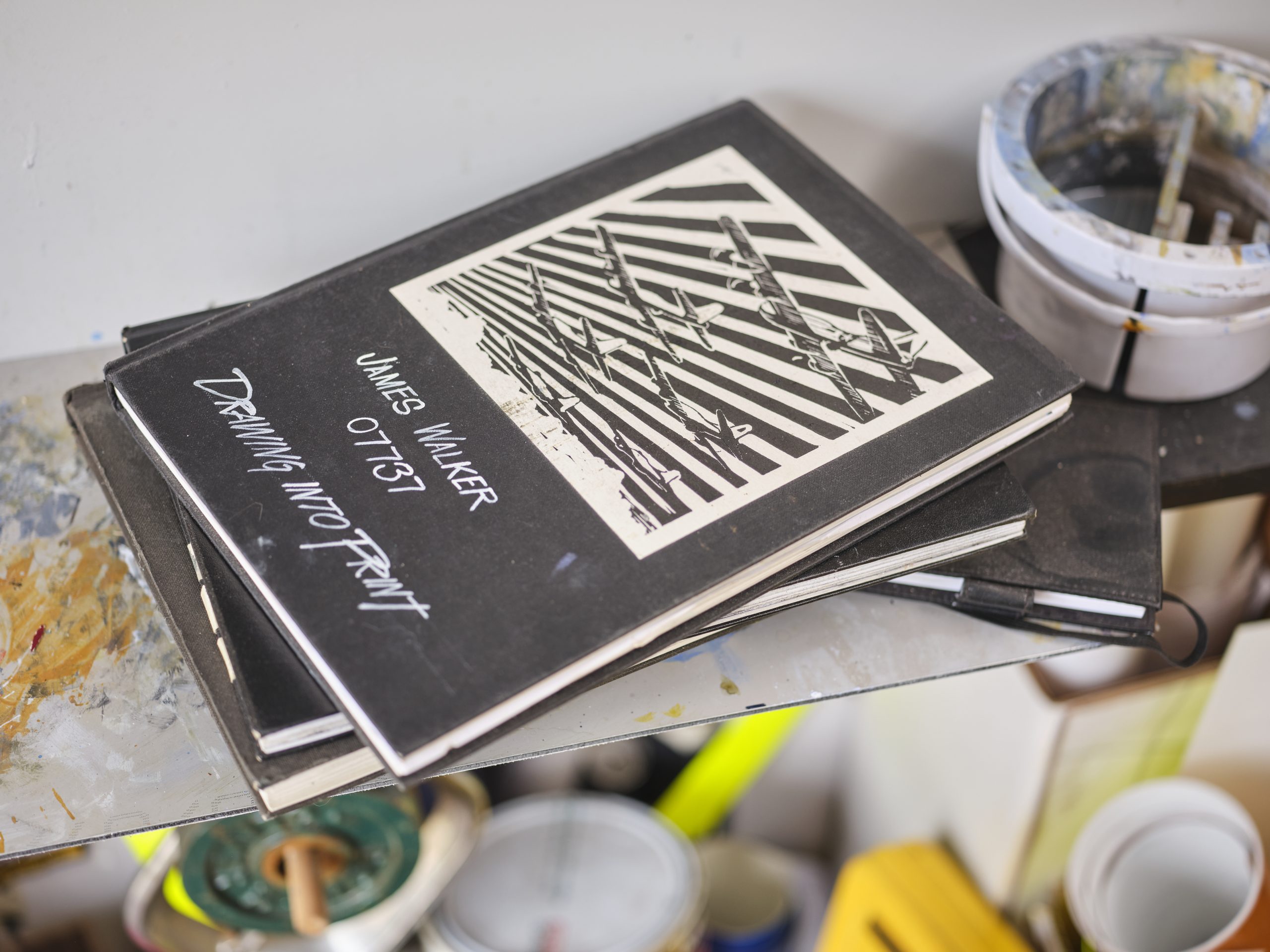

James Walker in his home studio, 2022. Photography by Duncan Wright

The sky has always fascinated James, and for many years he lived under a busy flight path in Launceston, Tasmania. “It was right above our heads” he shares, “There was constant airline traffic. So you’d see this sort of backwards and forwards movement, whether it was the planes themselves, or watching the power lines as they roll over the hills”.

As a child James was obsessed with all sorts of machines and objects, and he loved to draw planes, particularly WWII aircraft. “My father started flying model planes and would bring home the boxes. And I really liked that machine aesthetic. So that whole love for planes really stemmed from that, from these dramatic pictures that you’d see on the boxes of models” he shares.

This love for aircraft evolved into a fascination with the sky itself. James explains “When drawing the machines, I kind of had to get my head around clouds and atmosphere and distance. Then once I started considering the work more conceptually, the planes sort of left. They come and go still, but what I was really attracted to was that space within the sky and the atmosphere. So I like clouds, but I like those transitioning shapes and colours that almost border on abstraction. And that evocative sense of space, time and distance.”

References to a landscape or figures in his works slipped away, and he began to focus solely on the sky. “It’s just as important as the landscape. And it’s also a location marker. For instance, you can take a photo on your phone and just look at the information. You can record all those details with the idea that if anybody ever wanted to, they could look up the coordinates I’ve put on paintings and search out the locations.” In Plane Spotting: Traverse 30 days this information looks like GPS coordinates, or dates and times. James likens them to journal entries, for example:

Saturday 24th November.

A very clear day. I played at a wedding in Calista (Kwinana). There was quite a lot of activity in the air. Aeroplanes and helicopters. Sky was without clouds and quite warm.

Having relocated five years ago to Western Australia, James often reflects on life in Tasmania. “I miss the landscape,” he says, “There’s something about it that is kind of ancient and wild. I miss the drama in the landscape. The difference say between Mandurah and Launceston, is Mandurah’s all on one plane, and Launceston is a valley. So you’re either below the landscape or above it or somewhere in between. So you can almost be in the sky and look across it, rather than just looking up at the sky and the sky kind of trailing off to the horizon.” The light in the west is also different. James described it as “so bright, like an assault on my senses”.

“So I think I paint with a Tasmanian aesthetic and palette. It is more subdued. There’s a particular vibrancy and colour that you get over there. I do like to knock the colour out a bit, and grey things up. And not that Tasmania’s dreary, it’s probably just greyer, more subdued.”

This approach to colour and light could be seen as an attempt by James to ground himself in the familiar atmospherics of Tasmania. A way of articulating — and holding onto — a sense of place, a memory or a feeling. Similarly, photography is used by James as a kind of reflective tool; a way to revisit a particular time and place.

“I like to take lots and lots of photographs wherever I go. And not because I want to paint every photograph, it just helps to embed it in your brain. How you felt at that time and what made you stop in that place. I’m very nostalgic and I probably dwell on the past more than I should, but I really love the idea of memory and the residual effect of memory and then using that.”

James will often take multiple photographs and merge them together in the studio to create his paintings. “I’ll take what I want from the photos,” he says, “I’ll shift and squeeze and then even in the painting process, I’ll be adjusting along the way. The painting must work on its own. And the photograph again is just, maybe I need to get a bit of an understanding of tree shapes or that sort of thing. Or maybe I want a landscape with a low horizon, with some of these silvery-white areas of water, then the photograph is good for that. But I don’t copy colours exactly or things like that, which you can get caught up in. Sometimes it’s an exercise in going “how far can you go?” Not trying to make it photographic, but probably just realistic. And I always find that phrase ‘It looks like a photo’, a bit bizarre because it’s not supposed to look like a photo. It’s supposed to look like life, and just evoke some kind of feeling” he shares.

James’ disciplined, highly poetic practice spans more than twenty-five years. He views painting as “this thing where you don’t do it because you built the skills up to do it. You just have to do it regardless and if you’re lucky, you’ll build some skills up along the way. So every painting’s still an experiment for the next. I keep saying this quote over and over, that was shared with me years ago. It’s the idea that art can make you nervous. And so I like the idea that you can look at a painting or artwork, or be creating one, and feel that little bit of excitement or that little flutter. There is a particular feeling, a way of applying paint, there’s a way of feeling it”.

James recently got his pilot’s license which, he shares, has offered him a new perspective on the sky, the landscape and no doubt his sense of place in WA. James’ solo exhibition Traverse is currently on view at Lost Eden in Dwellingup, and his work can be seen in The Alternative Archive again in Carnarvon and Bunbury.